The novel coronavirus was working its way through the United States, and Blauer — along with dozens of colleagues at Johns Hopkins University — was actively tracking its path.

“The sirens now feel different,” she said recently. “They come with a different flood of emotions.”

The noise outside her window was a tangible reminder of the human lives hidden in the maze of anonymous data that had come to dominate her days.

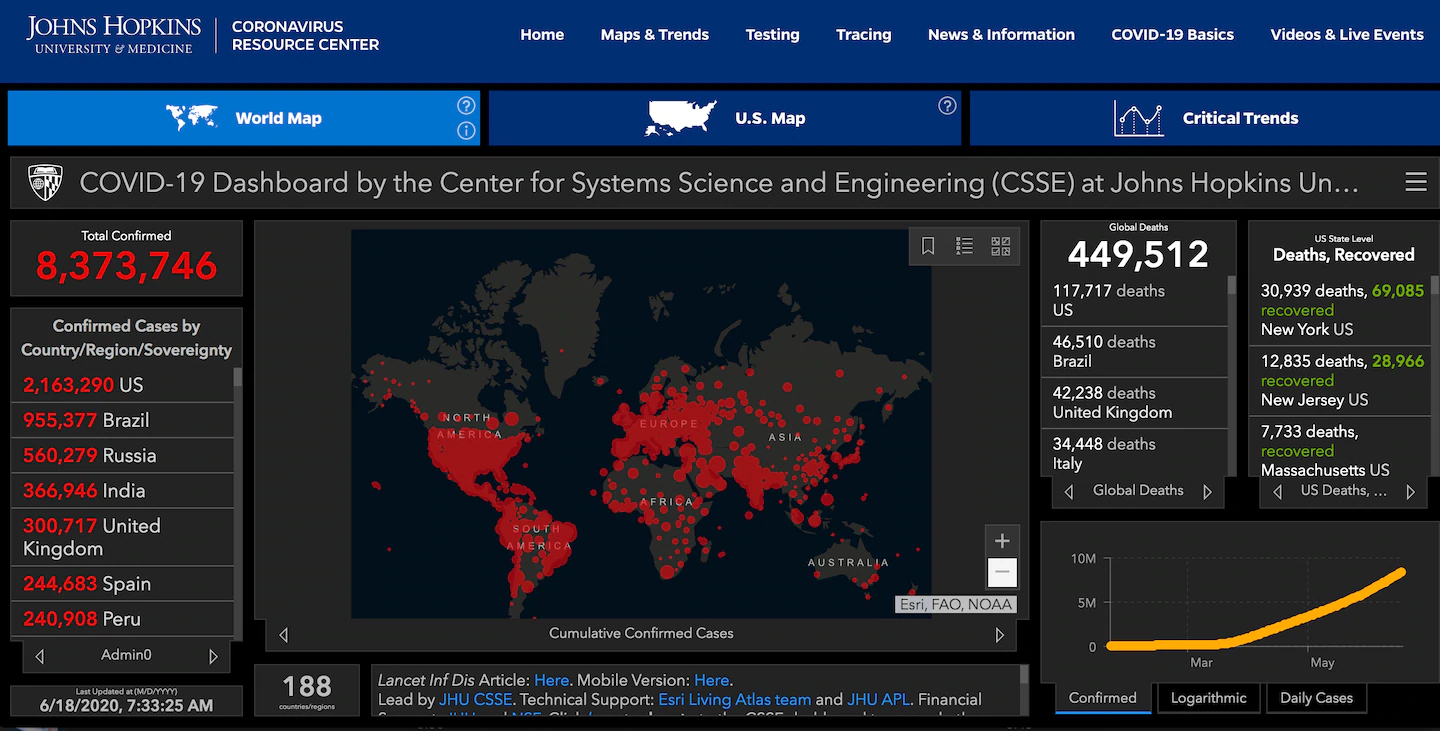

Since launching in January, the university’s Coronavirus Resource Center has exploded in scope and popularity, garnering millions of page views and popping up in news coverage and daily conversation. Through numbers, the tracker has told the story of what the virus is doing while the story is still unfolding, offering a nearly real-time picture of its silent march across the globe.

But even as data has jumped to the forefront of international discussions about the virus, the Johns Hopkins team wrestles with doubts about whether the numbers can truly capture the scope of the pandemic, and whether the public and policymakers are failing to absorb the big picture. They know what they are producing is not a high-resolution snapshot of the pandemic but a constantly shifting Etch a Sketch of the trail of covid-19, the disease caused by the virus.

Case counts are consistently inconsistent. Reporting practices differ from country to country, state to state, even county to county. If authorities fail to contextualize the virus with other factors — such as Zip codes, race or Medicaid usage — the hardest-hit communities can go unseen.

“Numbers in some ways instill this sense of comfort. But then on the other hand, they can be wrong,” said Lauren Gardner, the associate professor at Johns Hopkins’s Whiting School of Engineering who has spearheaded the global tracker since Day 1. “And they can be wrong for lots of different reasons.”

For those looking closely, the Hopkins project does lay out a clearly legible story about American life today, one involving economic inequality, racial disparities and poor access to health care. Many of the same issues flared up in street protests after the May 25 killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis police custody, an incident that sparked civil unrest and temporarily pushed the pandemic off the country’s front pages.

The tracker data can offer a bridge between the two news cycles, those working all hours to maintain it say. And as cases again begin to spike in the South and West, the Johns Hopkins project remains a key resource for understanding the virus’s impact.

“This is the first time data has been such a central part of the narrative,” said Blauer, the executive director of Johns Hopkins University’s Centers for Civic Impact. “The human connection — I think we need more of that in the larger national narrative. It just feels like the compassion is getting lost.”

Launching the project

It started over coffee.

The virus had clouded Ensheng Dong’s thoughts all January. Every time the first-year PhD student called home to China’s Shanxi province, he heard about the sickness spreading from Wuhan.

Dong modeled outbreaks as part of his studies. He had lived through China’s 2003 outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome, or SARS. Combing the available Chinese statistics, he realized each data point could be a former classmate or neighbor or family member.

So when Gardner, his adviser at Hopkins, suggested that Dong create a map to track the global reach of the infection, he readily agreed.

“I wanted to use my experience to collect data to show the public,” Dong said. “And the first member of the public was me.”

Gardner, an expert in modeling infectious-disease spread, initially had a fairly modest vision for the project. She knew disease reporting — or how authorities track and publicize the numbers — is inconsistent. She figured that by noting the data in real time, she and Dong could provide academic colleagues with statistics for later analysis.

“When we started this there was not a single dedicated covid-19 tracking website by a public health authority anywhere,” she said.

Dong went straight to work. For 12 hours, he collected data, translated information from Chinese, designed tables and bulldozed the statistics into a program that would create a map. His stark aesthetic choices — black for the background, red for dots indicating infections — were deliberate: “I wanted to alarm people that the situation was getting worse.”

The next morning, Jan. 22, Dong showed Gardner his results. After a few tweaks, the project went live, with red dots ballooning across countries — and states and provinces, when possible — to show numbers of known cases, and charts listing confirmed cases and deaths for each jurisdiction.

Gardner and Dong fished through media reports and Twitter accounts for updates, manually punching in the new figures. Early on, as the virus spread to Japan and South Korea, the project was a crowdsourced effort, with people from around the world emailing about new cases. The data feeding into the dashboard was open to the public in a Google Sheets file, so anyone could click through the numbers and pinpoint mistakes or offer suggestions.

As the potential dimensions of the disaster took shape — millions sick, widespread lockdowns, a scorched-earth global economy — the public looked to the tracker to make sense of a frightful ordeal.

I’ve gone a whole day without checking the Johns Hopkins Coronavirus dashboard. (Anyone else obsessed with that thing?) Decided to go check out my garden instead. pic.twitter.com/FvU3lAqPsw

— Michelle Rheault (@rheault_m) May 15, 2020

Lainie Rutkow, a professor of health policy and management at Hopkins’s Bloomberg School of Public Health, was reminded of the public anxiety she witnessed in the days after the attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, a cataclysmic event that had rerouted her from a career in law to one in public health.

“That same type of uncertainty, I see now,” she said, “those feelings of uncertainty about what happens next.”

She joined the team with the idea that what Gardner and Dong had started could grow into a more ambitious tool, one that could not only track the virus but also explain and contextualize the spread for a global audience desperate for information.

At the same time, the mechanics behind the project were rapidly changing. In February, governments began releasing virus statistics. Rather than ease the workload, the shift revealed a major shortcoming: There was no international body laying out criteria for how to tally coronavirus infections or deaths. Each country put out its own data, sometimes revising it weeks or months later in ways that dramatically changed the trends the tracker was trying to identify.

The pace of infection — faster every day — created more issues for the small team.

“Initially, I was trying to update it two to three times a day, at 12 p.m. and 12 a.m.,” Dong said. “But people were so anxious to see the dashboard, so I had to update every three to four hours. But sometimes by the time I had collected it all, the data had updated in the original data source, so I would have to tear down everything I’d done and collect it again.”

Charting inequity

Blauer first pulled up the tracker out of personal caution. It was February, and she was supposed to travel to Israel and India soon.

As she scanned the dashboard, Blauer recognized that what her colleagues were building hit on concerns central to her work at the Centers for Civic Impact, which helps local and state governments use data in decision-making.

She contacted Rutkow and asked to join the team.

Her own plunge into data started after college, when Blauer worked as a juvenile probation officer in Baltimore.

She would get called to police stations in the middle of the night and asked to determine whether a child who had just been arrested could go home with family or needed to spend the night in jail.

“I was asked to make a decision in the lives of these kids based on no information,” she said. “I didn’t know if the child had been in school that day, if they had access to food at home, if there was a social worker involved with the family.”

There had to be a better way, she decided.

In 2004, she became a key player in then-Mayor Martin O’Malley’s CitiStat program, a data-driven effort to track and monitor municipal work.

When O’Malley (D) became governor, Blauer ran a similar statewide effort from Annapolis, tracking everything from infant mortality rates to budget spending. The large-scale effort — one of the first of its kind in government — “became a kind of religion,” she said.

The experience schooled Blauer on the nitty-gritty complexities of American inequity. Any given Zip code was layered with the historical baggage of past policies. Discriminatory housing, health-care access, school stability — they were all baked in.

So when Blauer and others began plotting a U.S. dashboard to complement the global tracker in March, they decided a simple tally of infections and deaths would not be enough to fully explain what the virus was primed to do to black, Latino and Native American communities.

The team settled on three areas of additional information for each county in the United States. The first was health-care capacity — not only the number of intensive care unit beds and staffing statistics but also how people accessed the local health-care system, whether through private insurance or Medicaid. Next, they decided to add information on the demographics of each county, including a racial breakdown, unemployment figures and age distribution.

The third focus was comparing county disease data against the state’s as a whole. The goal was to measure whether the virus posed an equal-opportunity risk or whether all that historical baggage would determine who lives and dies.

The U.S. map went live in mid-April and was quickly complicated by inconsistencies in how different jurisdictions presented data.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention had just changed its guidance, suggesting that local health officials include probable deaths and probable infections in their counts. Some states did. Some didn’t. Sometimes some counties within a state would follow it and others would chart a different course.

“It’s one thing that this is not consistent globally, that Spain presents data differently from Indonesia, and Indonesia reports differently from the U.S.,” Gardner said. “The thing that’s crazy to me is how different the reporting is within a state in the United States, let alone state to state.”

By then, Johns Hopkins, like the rest of the county, was shut down. The tracker team — which now comprises dozens of professors, experts and students from multiple departments — coordinated via long Zoom meetings, emails and phone calls.

“The first 6 1/2 weeks, we were building the plane as it flew, and we were flying at supersonic speeds,” said Sheri Lewis, a member of Hopkins’s Applied Physics Laboratory working on the tracker.

The U.S. map soon illustrated what anecdotal reports were suggesting: Minority communities were being hit hardest by the disease.

In Washington, D.C., African Americans accounted for 46 percent of the city’s population but 74 percent of deaths. In Arizona, Native Americans — who make up about 5 percent of the population — accounted for 18 percent of deaths. And in South Dakota, where African Americans are less than 3 percent of the population, they represented 17 percent of coronavirus cases; other minority populations totaling around 16 percent of the population, including Latinos and Native Americans, made up 70 percent of cases.

For Gardner, the U.S. map put a spotlight on inequalities that made the pandemic more heartbreaking.

“When you actually start looking at the affected populations, the breakdown of race and age and ethnicity and socioeconomic demographics, it becomes so much more human,” she said.

Even Blauer, who has spent her career teasing out the social ills hidden inside strings of numbers, felt frustration and resignation as she watched the virus’s path.

“We’ve known for generations that populations that are poor and living in highly dense areas have these co-morbidities that are presenting for risk for covid-19,” she said. “But the reality of the situation is we don’t do anything about it. If you are born black in this country, it’s harder for you to get a job, harder for you to keep a job and also harder for you to stay alive.”