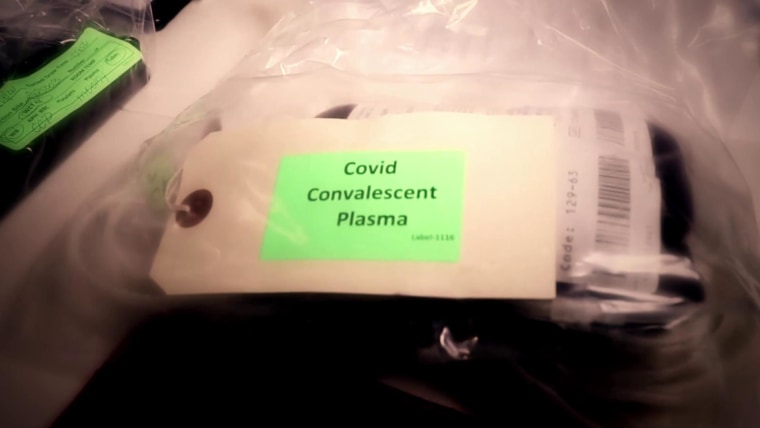

Transfusions of plasma from people who have recovered from COVID-19, the illness that SARS-CoV-2 causes, appear to be safe for severely ill patients and may speed their recovery, according to a preliminary study.

For more than 100 years, doctors have used convalescent plasma (a component of blood) from people who survived life threatening infections to treat others.

The idea is that antibodies against a bacterium or virus remain in the blood of someone who has recently recovered from the infection.

Doctors used convalescent plasma as a treatment during the 1918 Spanish flu pandemic and had varying degrees of success with it during the 2003 SARS outbreak, the 2009 swine flu (H1N1) outbreak, and the 2014 Ebola outbreak in Africa. In 2015, scientists established this treatment as the protocol for Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS).

Early in the COVID-19 outbreak, on January 20, 2020, doctors in China began treating severely ill patients with convalescent plasma. They reported encouraging results from five cases in the journal JAMA.

On March 28, 2020, Houston Methodist Hospital in Texas became the first academic medical center in the United States to treat critically ill COVID-19 patients with convalescent plasma.

“While physician scientists around the world scrambled to test new drugs and treatments against the COVID-19 virus, convalescent serum therapy emerged as potentially one of the most promising strategies,” says Dr. James M. Musser, chair of the Department of Pathology and Genomic Medicine at Houston Methodist.

Between March 28 and April 14, Dr. Musser and his colleagues enrolled 25 people with severe or life threatening COVID-19 into a preliminary study to investigate the safety of the therapy.

Nine of the participants (36%) showed an improvement in their condition after 7 days, and 19 (76%) had improved or been discharged after 14 days.

There were no adverse events that the researchers could attribute to the therapy.

They report their findings in The American Journal of Pathology.

One of the concerns that people have regarding the safety of convalescent plasma is that it may contain infectious agents, including the pathogen that it should be treating.

The authors report that the donors in their study had fully recovered and been asymptomatic for at least 14 days.

In keeping with standard practices for donating blood, the researchers also screened the plasma for a range of other pathogens, including hepatitis B and C, HIV, Chagas disease, West Nile virus, Zika virus, and syphilis.

They say that more than 150 individuals who had recovered from COVID-19 donated their plasma to help treat others, and many continue to do so.

“We are deeply indebted to our many generous volunteer plasma donors for their time, their gift, and their solidarity.”

– Study authors

The researchers note that the rate of clinical improvement among the people who received the plasma was on a similar scale to the improvement that scientists reported in studies of the antiviral drug remdesivir.

However, they emphasize that the primary goal of their research was to gauge the safety of the treatment rather than its efficacy.

The study was small, there was no control group, and the participants received other experimental treatments. For example, 68% of them received the antiviral ribavirin, and they all took the antimalarial drug hydroxychloroquine.

Notably, the authors report that there was no clear correlation between the amount of COVID-19 antibodies in infusions of donated plasma and the outcome for those who received them.

The study may have been too small to show a significant association of this kind, known as a “dose response.”

Houston Methodist is considering a larger, randomized controlled trial of the therapy.

Other, multicenter studies of convalescent plasma are currently underway.

In May, a collaboration between 57 medical institutions in the U.S. — called the National COVID-19 Convalescent Plasma Project — reported in a preprint that the therapy appears to be safe.

Last month, one of its founders, Dr. Arturo Casadevall from Johns Hopkins University, told Medical News Today that close to 12,000 COVID-19 patients in the U.S. had already received the treatment.

However, he was concerned that patients were not getting the therapy early enough because it is currently only approved for cases that are serious or life threatening.

An infusion of antibodies against the virus to enhance the body’s immune response may be more effective earlier in the illness.

The reason for this is that by the time a person becomes severely ill, their immune system has gone into overdrive, resulting in inflammation of the lungs and then an excessive release of immune factors, known as a “cytokine storm.”

For live updates on the latest developments regarding the novel coronavirus and COVID-19, click here.