A Maryland man believes he could be one of the first people successfully vaccinated against coronavirus after his body produced antibodies in response to a trial.

David Rach hailed the ‘promising’ results from a trial at the University of Maryland in Baltimore, where US drugs giant Pfizer and German firm BioNTech are gearing up to mass-produce the vaccine if it proves effective.

Rach, a graduate immunology student at the university, said his body was generating more antibodies than the levels seen in recovering virus patients after he was the first person injected in the trial.

However, it will be months before the results can be fully assessed, because scientists need to know how long the antibodies will last and whether Rach will prove immune to the virus if he encounters it in the meantime.

Scientists around the world are racing to develop a vaccine, which is seen as the only certain way to bring the pandemic to a standstill and allow life to return to normal if it is reliable and widely enough distributed.

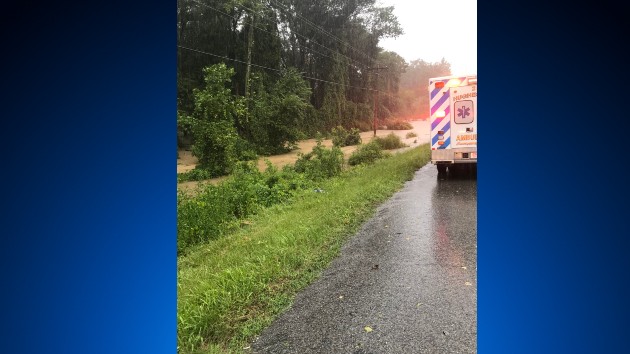

David Rach – pictured being injected with a trial vaccine at the University of Maryland – says he could be one of the first people successfully inoculated against Covid-19

Health experts are still not certain about how much immunity is acquired naturally from a battle with the disease, meaning that hopes of achieving herd immunity are fraught with uncertainty.

After receiving two doses of a trial vaccine, Rach said that ‘the early data results are indeed positive’ but warned that there is still a ‘long road ahead’.

Rach does not believe he has had the virus, pointing out that it would be useless to test a patient who might already have developed antibodies.

He also does not know for sure whether he was administered with the trial vaccine or a placebo saline solution, but believes that his body has been generating ‘Sars-COV-2 Spike Protein RBD specific antibodies’ in the wake of the test.

‘It’s promising. Even despite being in the low dose group, I generated higher Sars-COV-2 Spike Protein RBD specific antibodies than the levels that are seen in the recovering COVID patients’ samples,’ he said.

But he added: ‘Does this mean I go around and start to licking doorknobs? Absolutely not.’

Rach will be back in the clinic in October to have his antibody levels checked, or earlier if he believes he has been expose dto the virus before then.

‘I take my temperature every morning and self report any COVID-related symptoms that I might be having,’ he explained.

David Rach, a graduate immunology student at the university, said his body was generating more antibodies than the levels seen in recovering virus patients

He said that everyone involved in the study is continuing to practice masks and social distancing because the effectiveness of the vaccine remains uncertain.

He added: ‘While generating higher antibody levels are encouraging, with this being a new virus scientists are still determining what immune protection [being] infected by the virus consists of.

‘Even if the vaccine turns out to be protective against COVID-19, if the immune response it generates is short lived, instead of bam, you’re vaccinated, you are now good for life [like with a Yellow Fever vaccine], you would need to get the vaccine more regularly to protect the individual.’

The Maryland project is one of many around the world which are hoping to make the decisive breakthrough against the pandemic.

Dozens of vaccine candidates are at various stages of development around the world to tackle the coronavirus pandemic.

One major trial is taking place at Oxford University in the UK, where the first human patients were injected with a trial vaccine in April.

Other trials are taking place in China and India among other countries. The head of India’s top clinical research agency recently claimed it could have a vaccine by August.

There are also concerns about how quickly a vaccine could be mass-produced and distributed once it is given the green light.

Health experts would have to deal with global travel restrictions while new kinds of vials and syringes may need to be invented for the billions of necessary doses.

Some developers are experimenting with new ways to mitigate the extreme cold storage demands of their vaccines, which currently need to be kept at -80C.

‘This is the biggest logistical challenge the world has ever faced,’ said Toby Peters, an engineering and technology expert at Britain’s Birmingham university.

‘We could be looking at vaccinating 60 per cent of the population’, meaning hundreds of millions of people in some countries.