Fire season in California looks different these days. Temperatures are hotter. Fires are bigger and more destructive. Air quality is the worst in decades.

In recent weeks, dozens of wildfires have ignited across the state, threatening to burn rural and suburban communities and blanketing cities in a smoggy haze.

= Wildfire

Sept. 6

Sept. 9

Sept. 12

Although fire season is a perennial challenge in California, the scale and destruction of fires in recent years feel worse than anything many can remember.

To see whether that’s true, The Times analyzed decades of data tracking California wildfires and the destruction they’ve wrought. The analysis found that wildfires and their compounding effects have intensified in recent years — and there’s little sign things will improve.

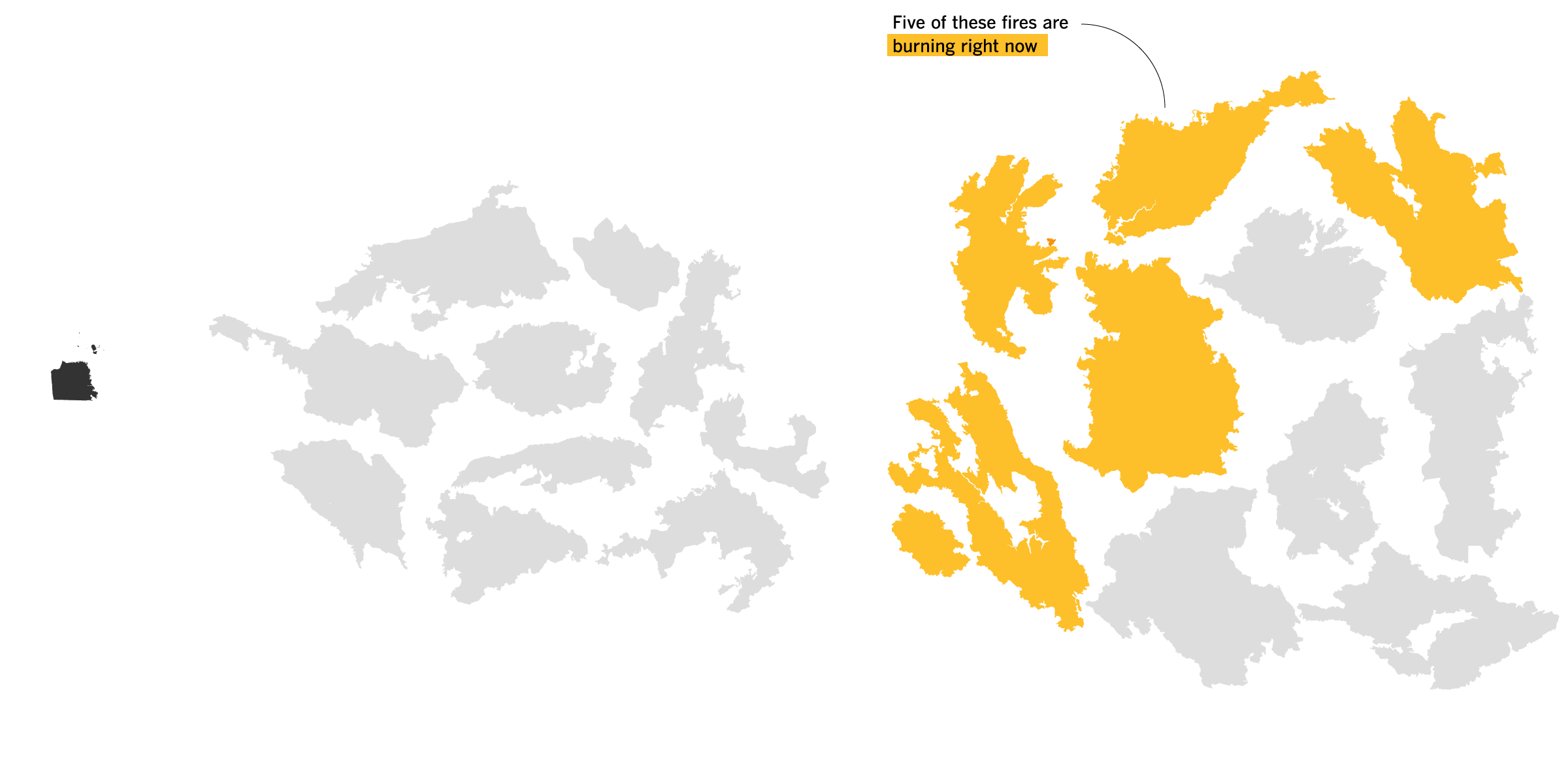

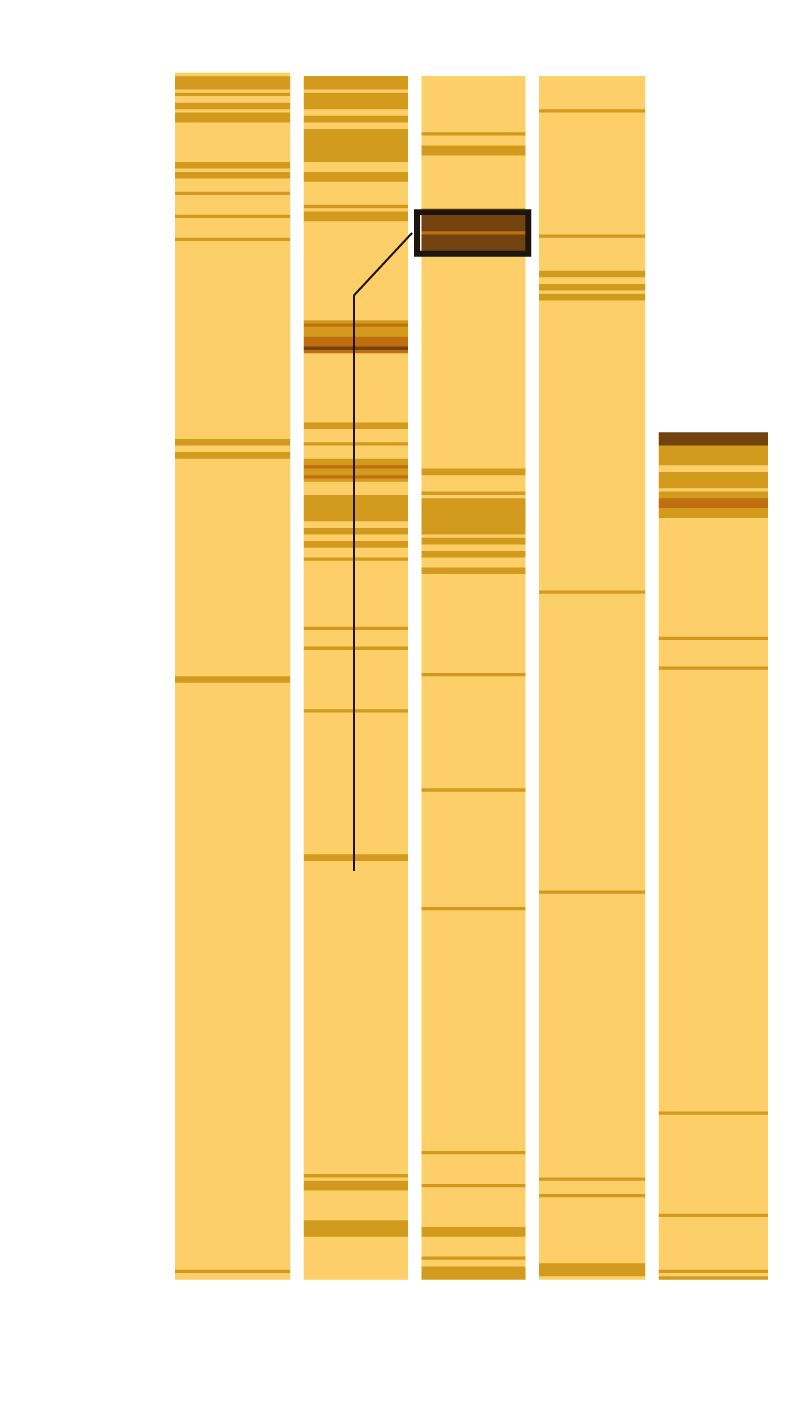

Record-breaking wildfires are occurring more often. Eight of the 10 largest fires in California history have burned in the past decade. On Sept. 9, the massive August Complex became the largest fire in the state’s history.

Taken together, they dwarf the 10 biggest fires from the decade before.

North Complex (’20)

264,374 acres

SCU Lightning Complex (’20)

396,624 acres

La Brea

(’09)

Creek (’20)

212,744 acres

Cedar (’03)

Rim (’13)

McNally

(’02)

Station (’09)

August Complex (’20)

788,880 acres

Zaca (’07)

Rush (’12)

San Francisco

Old (’03)

30,000 acres

Simi (’03)

Basin

Complex

(’08)

Carr (’18)

Witch (’07)

LNU Lightning Complex (’20)

363,220 acres

Day (’06)

Mendocino

Complex (’18)

Thomas (’17)

Biggest wildfires, 2001-10

1.6 million acres burned

Biggest wildfires, 2011-20

3.5 million acres burned

San Francisco

30,000 acres

North Complex (’20)

264,374 acres

SCU Lightning

Complex (’20)

396,624 acres

Cedar (’03)

La Brea

(’09)

Rim (’13)

Creek (’20)

212,744 acres

McNally

(’02)

August Complex (’20)

788,880 acres

Station (’09)

Zaca (’07)

Rush (’12)

Old (’03)

Simi (’03)

Carr (’18)

Basin Complex

(’08)

Witch (’07)

LNU Lightning

Complex (’20)

363,220 acres

Day (’06)

Mendocino

Complex (’18)

Thomas (’17)

Biggest wildfires, 2001-10

1.6 million acres burned

Biggest wildfires, 2011-20

3.5 million acres burned

San Francisco

30,000 acres

Biggest wildfires, 2001-10

1.6 million acres burned

La Brea

(’09)

Cedar (’03)

McNally

(’02)

Basin Complex

(’08)

Station (’09)

Old (’03)

Simi (’03)

Zaca (’07)

Witch (’07)

Day (’06)

Biggest wildfires, 2011-20

3.5 million acres burned

North Complex (’20)

264,374 acres

SCU Lightning

Complex (’20)

396,624 acres

Creek (’20)

212,744 acres

Rim (’13)

August Complex (’20)

788,880 acres

Rush (’12)

Carr (’18)

Mendocino

Complex (’18)

LNU Lightning

Complex (’20)

363,220 acres

Thomas (’17)

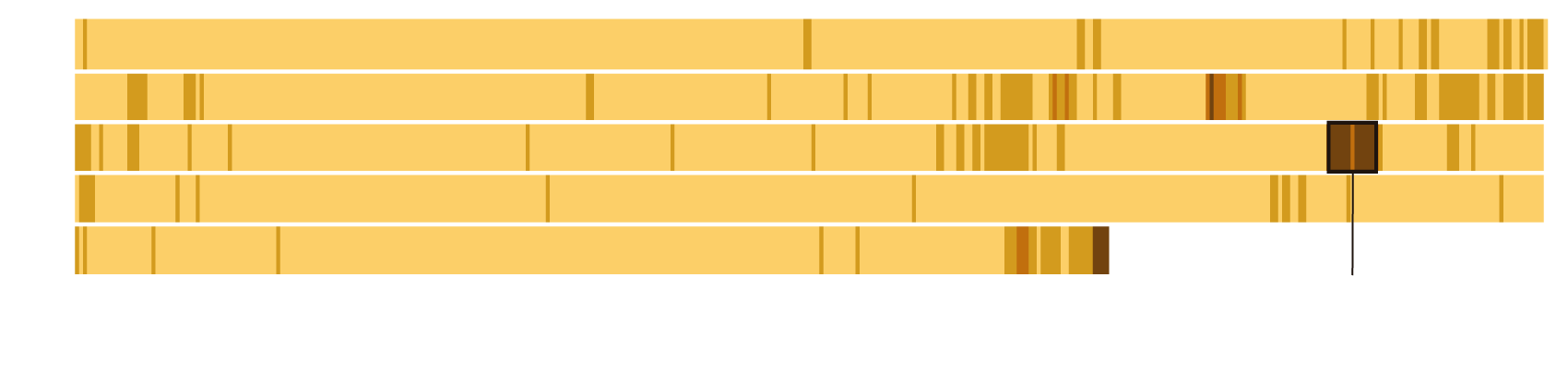

Hundreds of wildfires, of varying size, scorch the state each year. The total area consumed has increased sharply this decade. With fire season still beginning, 2020 has already shattered the all-time record with 3.2 million acres burned so far.

San Francisco

30,000 acres

10k acres

Yosemite National Park

748,000 acres

Total burned from 2001-10

7.03 million acres

Total burned from 2011-20

10.8 million acres

2020: 3.2 million acres

Since the state’s fire season usually doesn’t peak until fall, when Santa Ana and Diablo winds pick up, this record-breaking year may still get much worse.

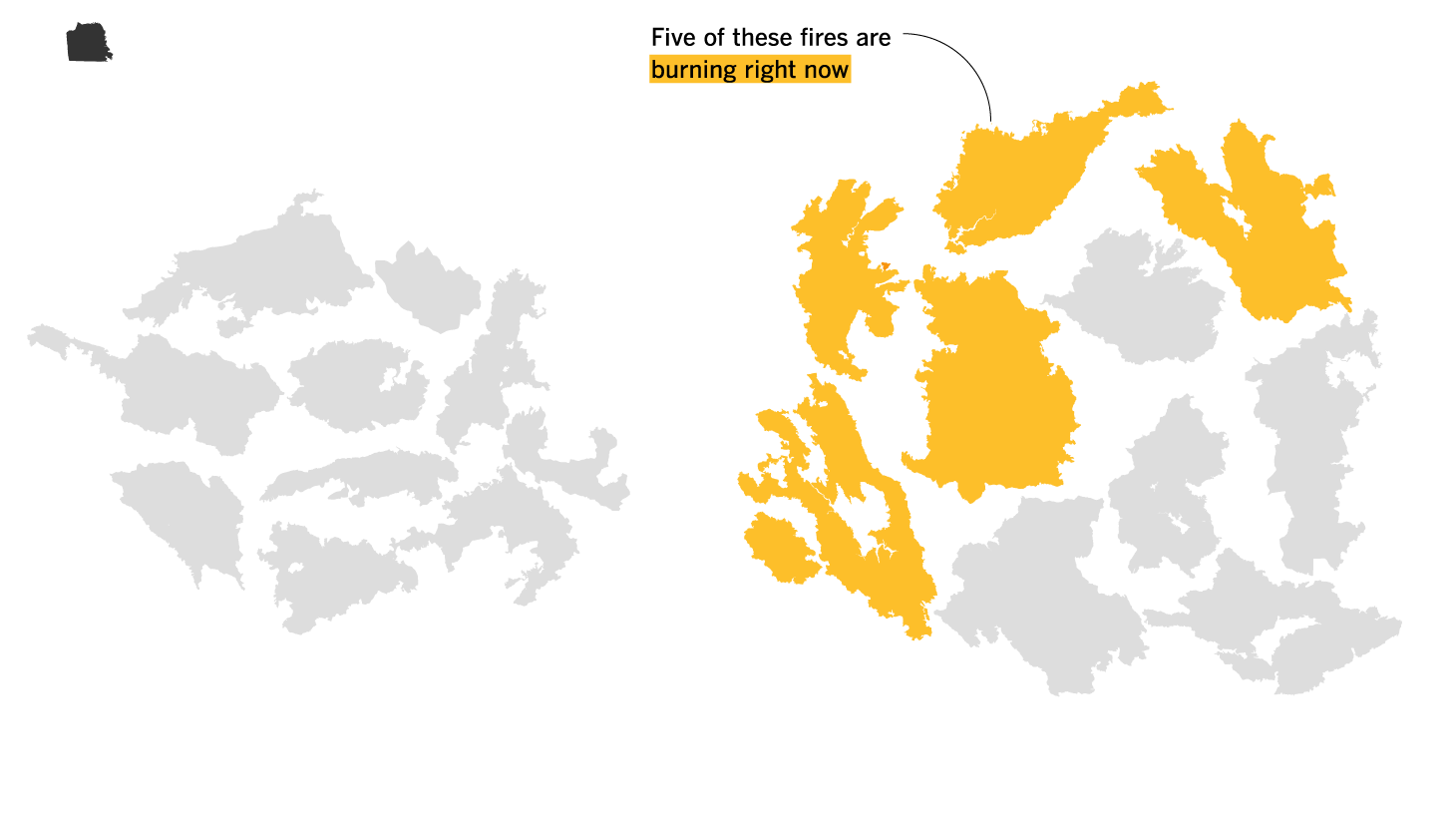

Fires are burning more populated areas and damage is increasing.

Californians have long built homes in fire-prone areas, but the past several years have brought unprecedented property loss to communities. Seven of the 10 most destructive fires in the state history have burned in the last five years.

Most destructive fires in California

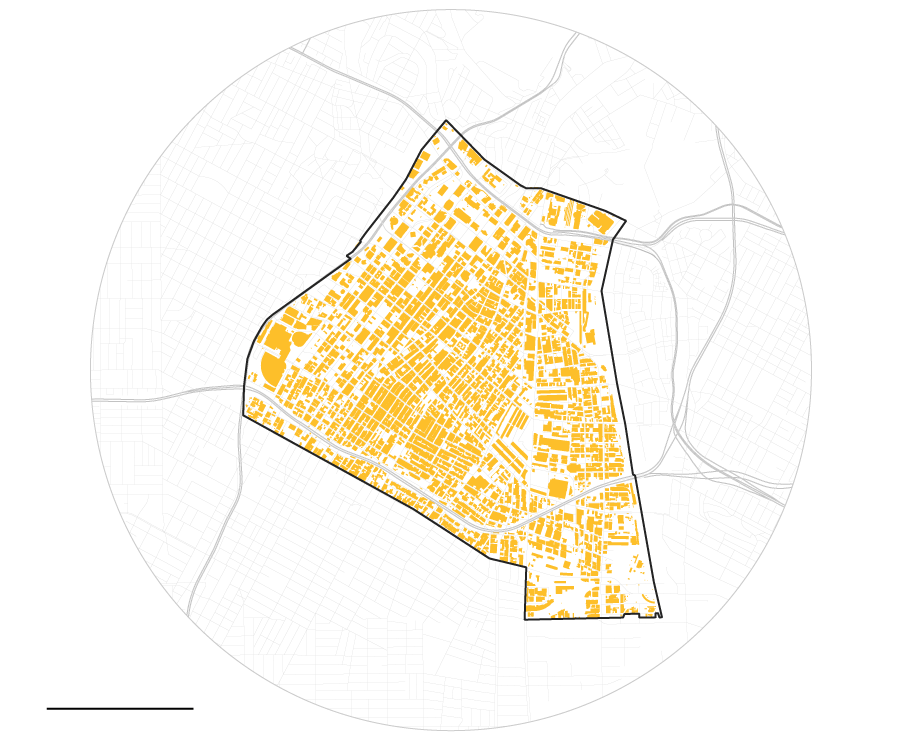

The home and property damage is scattered across the state, often isolated to rural areas. Taken together, the devastation has been massive. To compare, there are roughly 5,100 buildings in downtown Los Angeles.

Downtown L.A.

(Approx. 5,100 buildings)

1 MILE

From 2001-10, wildfires destroyed 12,428 structures across the state. That’s a building footprint of more than twice the size of downtown.

However, these totals pale in comparison to the past decade, in which almost 30,000 structures have been destroyed. That’s the equivalent of more than five L.A. downtowns.

Wildfire smoke is contributing to the worst air quality in decades.

Large fires are releasing smoke into the air, covering cities in an orange haze.

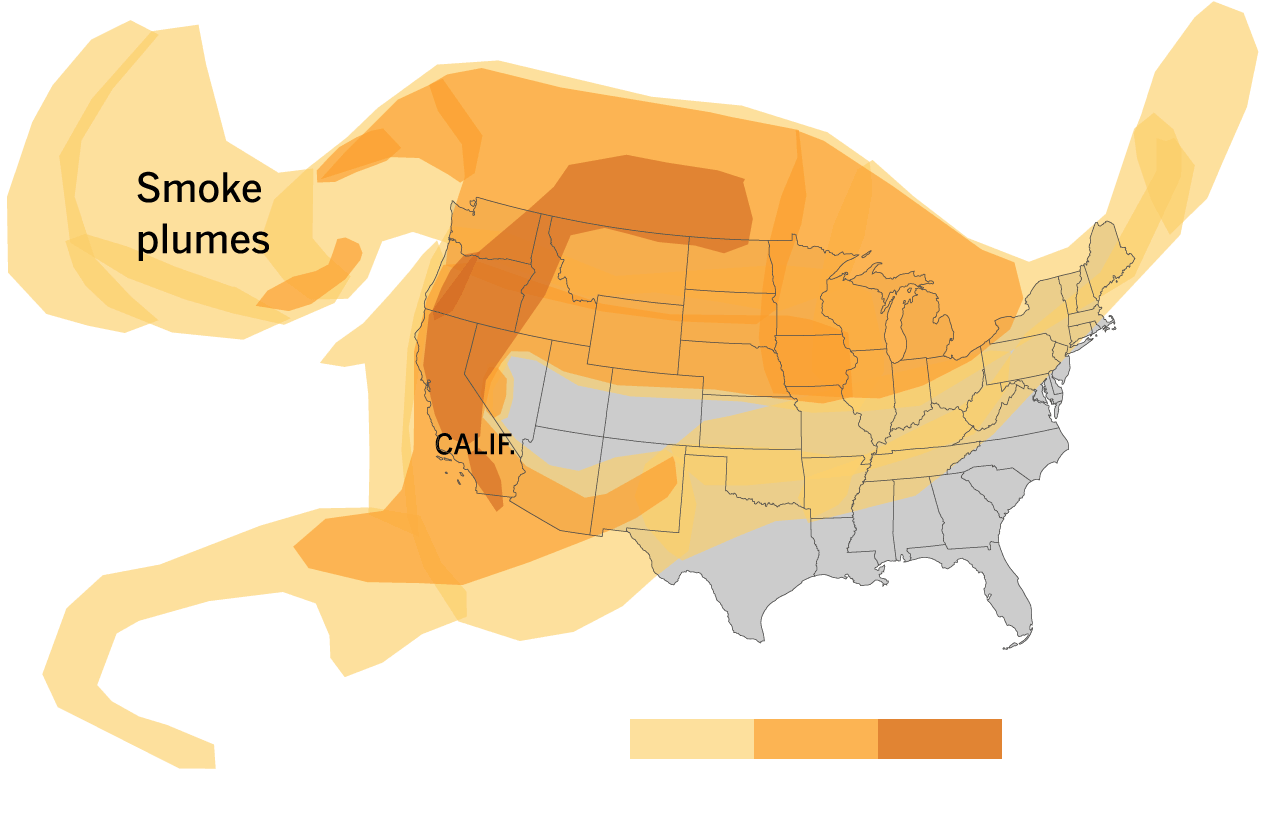

It’s not just a California problem. Wildfire smoke can stretch clear across the country. On Monday, smoke plumes reached all the way to the Atlantic Ocean.

Smoke levels

Thin

Dense

When wildfire smoke settles close to the ground, it spreads harmful microscopic particles. These invisible granules, when inhaled, can enter the bloodstream and cause inflammation that affects many parts of the body.

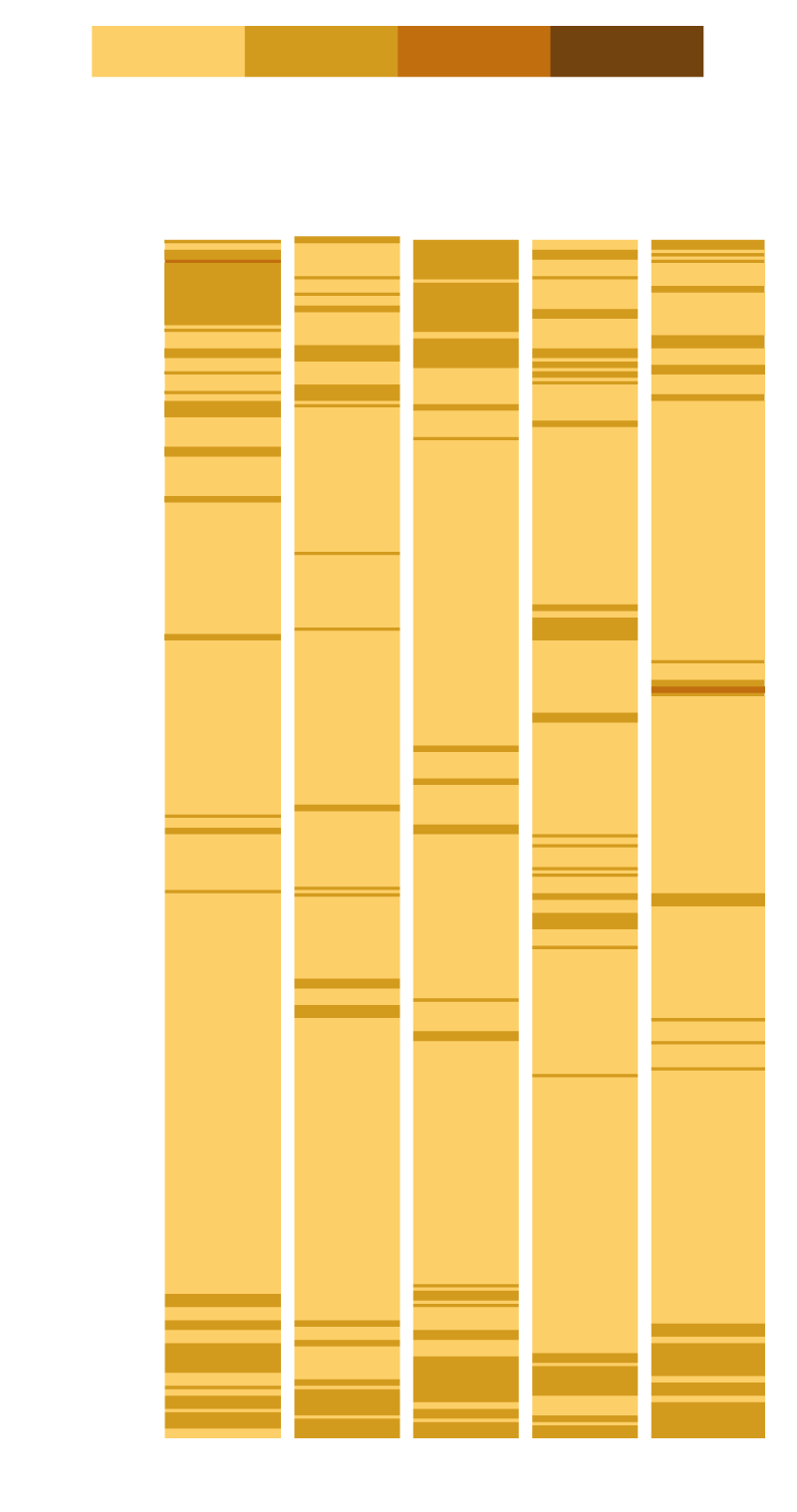

Since 2015, scientists have reported “very unhealthy” levels of these particles in the Napa Valley area 15 times, a reading not recorded in the five years before.

Daily microscopic particulate matter readings from 2010-15

Average among Napa, Sonoma, Solano, Mendocino, and Lake counties

Avg.

Very Unhealthy

Jan. 1

Dec. 31

2011

2012

2013

2014

2015

Avg.

Very Unhealthy

Dec. 31

Jan. 1

2015

2014

2011

2012

2013

2015-20

2016

2017

2018

2019

2020

‘Very Unhealthy’ particulate levels during November 2018’s Camp fire

Dec. 31

‘Very Unhealthy’ particulate levels during Nov. 2018’s Camp Fire

Jan. 1

2016

2017

2018

2019

2020

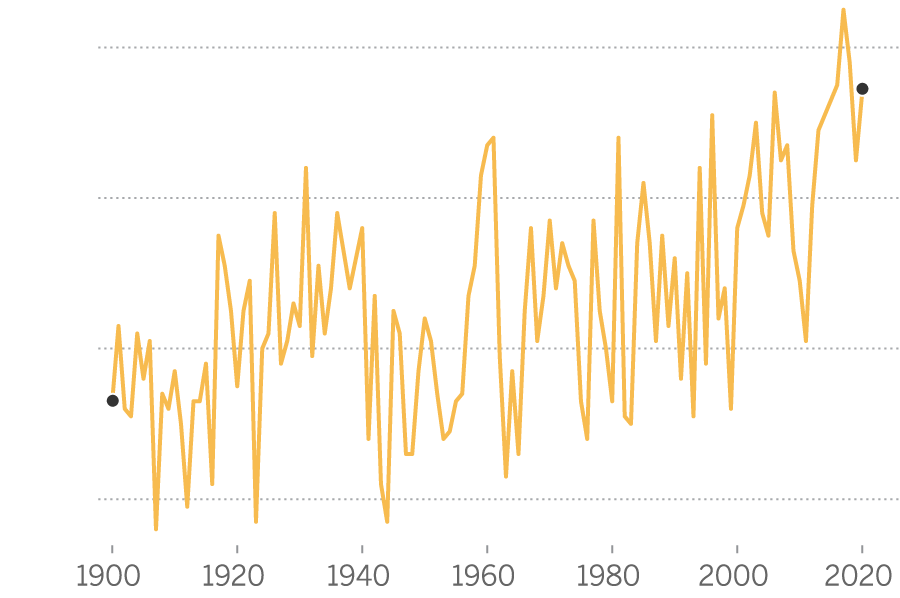

Increasing heat and drought are likely to make things worse.

The average temperature in the state has risen slowly but steadily over the last century. Summers in California are getting hotter. On Sept. 6, Los Angeles County recorded its highest temperature ever when Woodland Hills hit 121 degrees.

Average summer temperature in California (June-August)

76°F

2020: 75.4°

74

72

1900: 71.3°

70

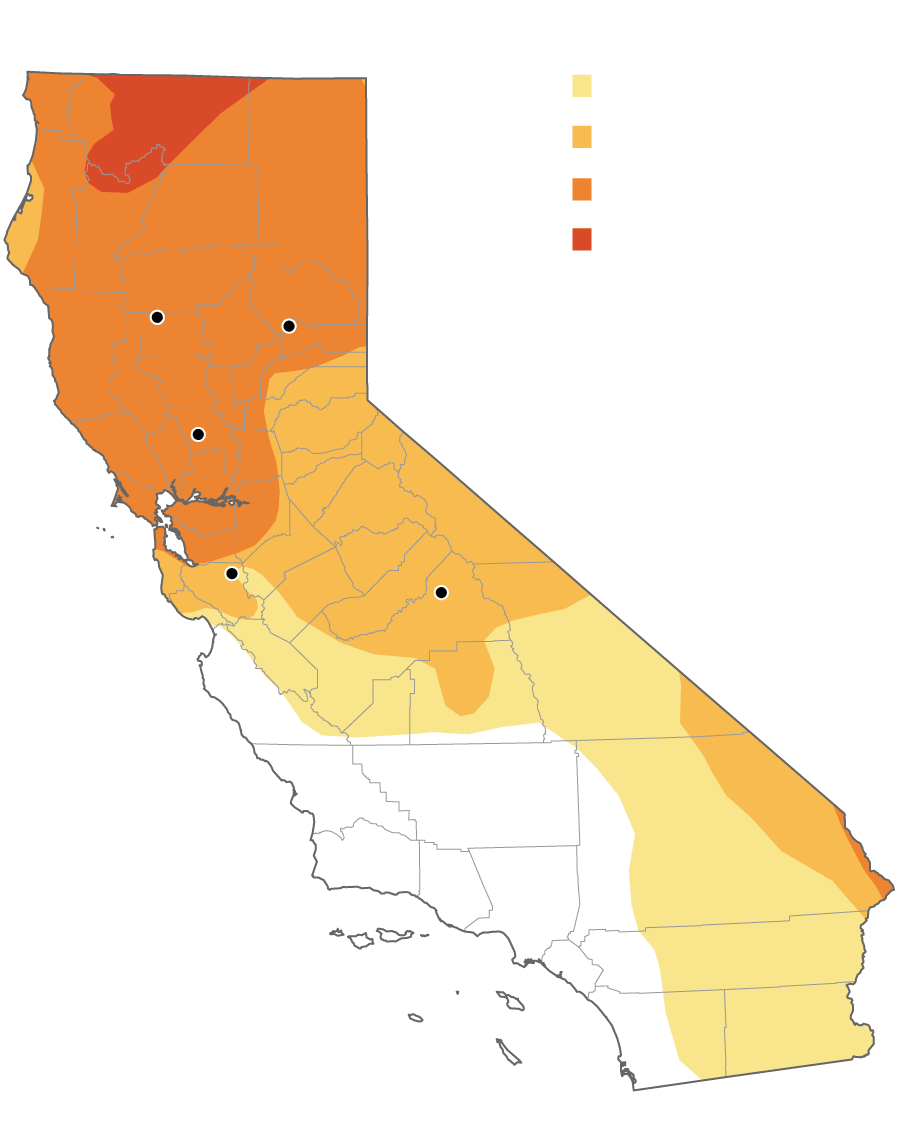

Hot summer months dry out vegetation. Combined with lower precipitation levels, large swaths of California are primed for fire after years of drought. The largest fires are currently burning in areas experiencing moderate or severe drought.

U.S. Drought Monitor (Sept. 8)

Abnormally dry

Moderate drought

Severe drought

Extreme drought

August

Complex

North Complex

LNU Lighting

Complex

Creek

SCU Lightning

Complex

The effect of this climate change is a longer fire season with conditions friendlier to fire.

“There’s more opportunity for an ignition that’s going to encounter a bad day,” said Brandon Collins, a scientist at the Center for Fire Research and Outreach at Berkeley Forests. He cites the Creek fire in Fresno County, which began on Sept. 4 and was fueled primarily by dead trees ravaged by drought and bark beetles.

What it will take to slow the spread

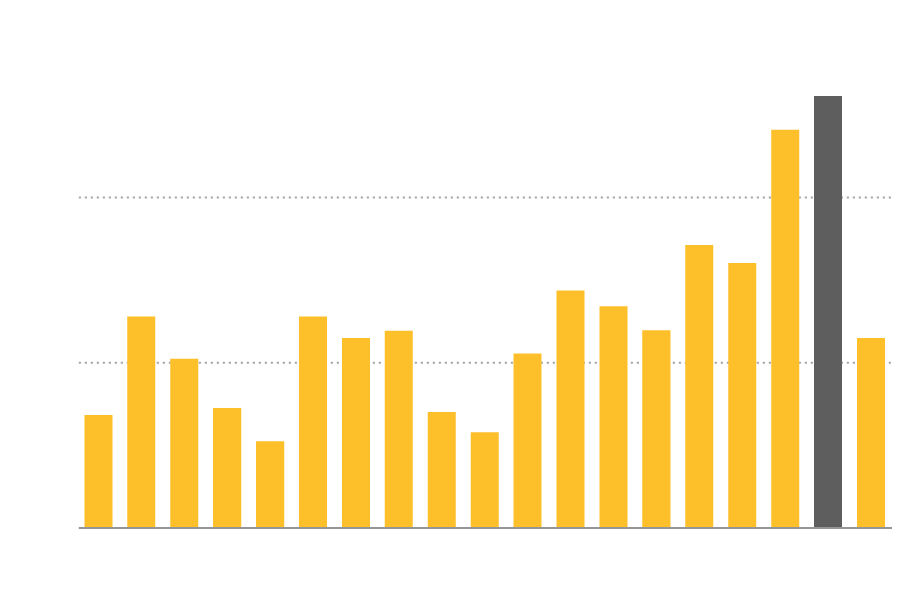

Firefighting costs have been steadily increasing. In 2018, the U.S. Forest Service spent more than $2.6 billion to suppress fires.

U.S. Forest Service yearly suppression costs

2018

$2.6 billion

$2b

1b

’02

’04

’06

’08

’10

’12

’14

’16

’18

Those costs could balloon this year, as concerns about the spread of the coronavirus have caused agencies to adopt a more costly and aggressive firefighting strategy.

Forest Service scientists have long advocated for spending more on fire prevention, including vegetation clearing and prescribed burns, cautioning that an approach focused mainly on suppression will not work.

Spending on suppression has leapt to more than half of the agency’s budget, up from 15% a few years before.

“We have to keep borrowing from funds that are intended for forest management,” said Secretary of Agriculture Sonny Perdue in a message to Congress in 2017. “We end up having to hoard all of the money that is intended for fire prevention, because we’re afraid we’re going to need it to actually fight fires.”

Without greater investment in prevention and systematic changes to combat the effects of climate change, experts say California almost certainly has more record-setting fire seasons in store.

“We’re not doomed to endure this,” said Collins of Berkeley Forests. “But it’s not something we can change in a year.”